ChatGPT: I love this question — it sounds simple, but it’s actually deeply layered.

When we say we have achieved harmony, we don’t mean everything is identical, quiet, or conflict-free. Harmony is coordinated difference, not sameness.

Here’s what harmony usually means across different levels of life:

1. In Music

Harmony is different notes sounding together in a way that feels whole.

Not the same note — that’s unison. Harmony is relationship.

Some notes create tension. Some create sweetness. But together, they form a coherent, meaningful sound.

👉 Harmony = difference arranged with awareness

2. In a Person (Inner Harmony)

A harmonious person isn’t someone with no struggle. It’s someone whose:

- Thoughts

- Emotions

- Values

- Actions

…are not fighting each other all the time.

You might feel sad but still act with kindness.

You might be afraid but still choose courage.

👉 Harmony = inner parts working together instead of pulling you apart

3. Between People (Relational Harmony)

Harmony in relationships does not mean:

- No disagreement

- No strong personalities

- No boundaries

It means:

- Differences are respected

- Tension is worked through, not avoided

- Each person can be themselves without threatening the bond

Like instruments in an orchestra — violin isn’t trying to become a drum.

Harmony = connection without erasing individuality

4. In Communities or Cultures

Harmony doesn’t mean one culture dominating or everyone thinking the same.

It means:

- Diversity is allowed

- Differences are coordinated toward shared well-being

- Conflict becomes creative adjustment, not destruction

Harmony is dynamic — always being tuned, like instruments before a concert.

Harmony = balanced coexistence with ongoing adjustment

5. What Harmony Is Not

Let’s clear this up, because people confuse these:

| Not Harmony | Why |

| Sameness | That’s uniformity, not harmony |

| Silence | Problems may just be suppressed |

| Obedience | Power imbalance isn’t harmony |

| Avoiding conflict | Avoidance creates hidden discord |

False harmony feels calm on the surface but tense underneath.

🌱 A Simple Core Definition

Harmony is when different parts remain different, yet fit together in a way that supports the life of the whole.

It’s not the absence of tension.

It’s the right relationship between tensions.

1️⃣ How to Tell Real Harmony from Fake Harmony

They can look similar from the outside — calm, polite, “everything’s fine.” But underneath, they’re completely different experiences.

🌿 Real Harmony Feels Like:

- People can disagree safely

- There is honesty without fear

- Differences are visible, not hidden

- Tension is addressed, not buried

- You feel relaxed in your body, not tight

There’s room to say:

“I see it differently.”

“That hurt me.”

“Let’s adjust.”

Real harmony has breathing space.

🎭 Fake Harmony Looks Like:

- Smiles, but unspoken resentment

- Politeness used to avoid truth

- One person or group shrinks to keep peace

- Conflict is treated like danger

- You feel like you’re walking on eggshells

Nothing explodes… but nothing truly connects either.

Fake harmony is fragile. Real harmony is flexible.

2️⃣ How Harmony Grows After Conflict

Here’s the surprise:

Harmony is often born from well-handled conflict, not from its absence.

Think of tuning a guitar string:

Too tight → it snaps

Too loose → it makes no sound

Right tension → music

Conflict reveals where things are out of tune.

🔥 When conflict destroys harmony:

- People try to win, not understand

- Pain turns into blame or punishment

- No one feels heard

- The goal is control

🌱 When conflict deepens harmony:

- Each side becomes more curious than defensive

- People ask: “What matters to you here?”

- Responsibility replaces accusation

- The relationship becomes more honest than before

After healthy conflict, there’s often:

- More trust

- More clarity

- Stronger connection

It’s like resetting a bone properly — painful, but stronger after healing.

Harmony that has never been tested is weak.

Harmony that has survived repair is resilient.

3️⃣ Why Harmony Always Includes Movement, Not Stillness

A lot of people imagine harmony as a peaceful, frozen lake.

But real harmony is more like a river — always adjusting.

🎵 In music

Harmony only exists because notes are moving somewhere.

🤝 In relationships

Needs change

Moods change

Life stages change

Harmony requires constant micro-adjustments:

- Listening again

- Rebalancing effort

- Re-negotiating boundaries

- Re-expressing care

When movement stops, harmony fades into:

- Stagnation

- Routine without connection

- Distance masked as stability

Harmony lives in ongoing responsiveness.

🌟 Bringing It All Together

| Living Harmony Means… | Not… |

| Safe truth | Forced niceness |

| Repair after rupture | Avoiding tension |

| Flexibility | Rigidity |

| Ongoing adjustment | “We figured this out once” |

| Stronger after strain | Fragile peace |

🌱 One Sentence Summary

Harmony is a living balance where differences stay present, tensions are worked with honestly, and relationships keep adjusting so the whole can thrive.

Not perfection.

Not quiet.

Not sameness.

______________________________________________________________________________

Here’s how to actively build harmony in a family, team, or community:

1️⃣ Start With a Shared “Why”

Harmony grows when people feel they are part of the same larger story, even if they play different roles.

Ask:

- What are we trying to protect or grow together?

- What kind of atmosphere do we want here?

Examples:

- Family → “A home where everyone feels safe to be themselves.”

- Team → “We succeed without burning each other out.”

- Community → “A place where differences contribute, not divide.”

👉 A shared purpose turns differences from threats into contributions.

2️⃣ Make Honest Expression Safe

Harmony requires truth — but truth needs safety.

Create norms like:

- “Disagreement is allowed; disrespect isn’t.”

- “Speak from your experience, not accusations.”

- “We listen to understand, not to prepare a counterattack.”

Simple practice:

When tension appears, shift from:

❌ “You always…”

✅ “When this happens, I feel…, and I need…”

Harmony grows when people don’t have to hide to belong.

3️⃣ Build a Culture of Repair

Every close group will mess up. Harmony depends less on avoiding mistakes and more on how quickly repair happens.

Normalize phrases like:

- “I think I misunderstood you.”

- “That came out wrong — let me try again.”

- “I’m sorry. I see how that affected you.”

Repair does three powerful things:

- Restores trust

- Reduces fear of future conflict

- Makes relationships more real

👉 No repair = slow emotional distance

👉 Regular repair = deeper harmony over time

4️⃣ Balance Voices and Power

Harmony collapses when one voice dominates or another disappears.

Watch for:

- Who talks most?

- Who rarely speaks?

- Whose needs get adjusted around?

Practical tools:

- In meetings: go-around so everyone speaks once

- In families: let quiet members finish without interruption

- In communities: rotate leadership roles when possible

Harmony needs inclusion, not just goodwill.

5️⃣ Respect Different Roles

In harmonious systems, not everyone does the same thing — and that’s good.

Some people are:

- Visionaries

- Organizers

- Caretakers

- Questioners

- Stabilizers

Conflict often comes from misreading differences as opposition.

Shift from:

“Why are you like that?”

to

“Ohhh, you play a different role in this ecosystem.”

Harmony grows when diversity of function is valued, not flattened.

6️⃣ Practice Ongoing Adjustment

Harmony is tuning, not a one-time agreement.

Create regular moments to ask:

- “What’s working well between us?”

- “What feels off lately?”

- “What small change would help?”

These check-ins prevent silent drift.

Small adjustments early avoid big ruptures later.

❤️ 7️⃣ Feed the Positive Bond

Harmony is not built only by solving problems — it’s strengthened by shared positive experiences.

Don’t just fix tension. Also:

- Celebrate small wins

- Share meals

- Laugh

- Express appreciation specifically

Tension shrinks when goodwill is actively replenished.

🌟 The Core Formula

**Shared purpose

- Safe honesty

- Regular repair

- Balanced voices

- Respected differences

- Ongoing adjustment

- Positive connection

= Living harmony**

Not perfect people.

Not constant agreement.

Just people committed to staying in right relationship with each other as life keeps changing.

🌿 Harmony Charter

A Shared Commitment to Living and Working Well Together

We recognize that harmony is not sameness, silence, or the absence of differences.

Harmony is created when diverse people stay in respectful, honest, and caring relationships.

Together, we agree to practice the following:

1️⃣ Shared Purpose

We remember that we are part of something bigger than any one person.

- We value the well-being of the whole as well as the individual

- We return to our shared purpose when tensions arise

We ask: What are we trying to protect or build together?

2️⃣ Respect for Every Voice

Every person here has dignity and something worth hearing.

- We listen without interrupting

- We make space for quieter voices

- We disagree with ideas without attacking people

Difference is welcome. Disrespect is not.

3️⃣ Honest and Kind Communication

Truth strengthens harmony when spoken with care.

- We speak from our own experience (“I feel…”, “I need…”)

- We avoid blame, labels, and assumptions

- We aim to understand before trying to be understood

4️⃣ Healthy Handling of Conflict

Conflict is natural. How we handle it determines whether harmony grows or breaks.

- We address issues rather than avoid them

- We stay curious about each other’s perspectives

- We seek solutions that consider everyone, not just winners and losers

Tension is a signal for adjustment, not a threat to connection.

5️⃣ Commitment to Repair

We accept that we will sometimes hurt or misunderstand each other.

- We are willing to say, “I’m sorry”

- We are willing to say, “That hurt”

- We forgive when sincere effort is made

Repair restores trust and deepens relationships.

6️⃣ Valuing Different Roles and Strengths

Not everyone contributes in the same way — and that is a strength.

- We appreciate diverse personalities, skills, and styles

- We avoid expecting others to be just like us

- We recognize that different roles can support the same goal

7️⃣ Ongoing Adjustment

Harmony is not a one-time achievement but a living process.

- We check in regularly about how we are doing together

- We stay open to small changes that improve our shared life

- We adapt as people and circumstances change

8️⃣ Nurturing Positive Connection

Harmony grows not only by solving problems but by sharing good moments.

- We express appreciation

- We celebrate progress

- We make time for warmth, laughter, and encouragement

🌟 Our Guiding Principle

We commit to staying in right relationship with one another —

honoring differences, speaking truth with care, and adjusting together so that all can thrive.

Any Difference between Harmony and Getting Along ? – Billy

ChatGPT said:

OHH yes — this is a great distinction. People often use them like they mean the same thing, but they’re actually very different levels of relationship.

Think of it like this:

Getting along is about smooth interaction.

Harmony is about right relationship.

You can have one without the other.

🌿 Getting Along = Low Friction

When people are getting along, things are:

- Polite

- Cooperative

- Not openly tense

- Functioning without obvious conflict

It’s about surface-level ease.

People getting along often:

- Avoid sensitive topics

- Downplay differences

- Prioritize comfort

- Stay in socially acceptable roles

It answers the question:

“Can we be together without trouble?”

That’s useful! Especially at work, in public, or with acquaintances.

But it doesn’t automatically mean depth, trust, or authenticity.

🎵 Harmony = Integrated Difference

Harmony goes further.

Harmony means:

- Differences are seen and included

- People can be real without threatening the bond

- Tension can exist without breaking connection

- The relationship actually becomes stronger through adjustment

It answers a deeper question:

“Can we stay connected while being fully ourselves?”

Harmony is not just smooth — it’s well-tuned.

🧭 Key Differences

| Getting Along | Harmony |

| Focus on comfort | Focus on wholeness |

| Avoids tension | Works with tension |

| Often surface-level | Involves deeper understanding |

| Fragile under stress | Strengthens through challenge |

| “Let’s not rock the boat” | “Let’s adjust the boat together” |

| Can hide differences | Makes space for differences |

❤️ Real-Life Examples

Coworkers getting along:

They’re polite, do their tasks, don’t argue… but never talk about what actually frustrates them.

Coworkers in harmony:

They can say, “Hey, our workflow isn’t working for me,” discuss it openly, and improve how they collaborate.

Family getting along:

No one brings up old wounds at dinner.

Family in harmony:

Hard things can be talked about without fear of losing love.

🌱 The Short Version

Getting along is peaceful coexistence.

Harmony is coordinated, honest, evolving connection.

Getting along keeps things from falling apart.

Harmony helps things grow together.

Moving from just getting along to real harmony is a kind of relationship maturity. And you’re right to ask what’s most essential — because many nice ideas help, but a few core practices make the real difference.

Here’s the honest answer:

The shift requires courage + care, practiced through ongoing honest adjustment.

Let’s break that down into what must be practiced most consistently.

1️⃣ The Courage to Be Real (Without Attacking)

Getting along often survives on politeness and self-censoring.

Harmony requires people to show up more truthfully.

This means practicing:

- Saying what you actually feel (without blame)

- Naming small tensions early

- Admitting when something matters to you

Not:

❌ “You never listen.”

But:

✅ “I felt unheard just now, and I want us to understand each other.”

Essential shift: From avoiding discomfort → to using discomfort as information.

Without this courage, groups stay shallow.

2️⃣ The Care to Stay Connected While Being Honest

Truth alone is not harmony. Brutal honesty without care breaks trust.

Harmony grows when people practice:

- Speaking firmly but respectfully

- Remembering the relationship matters more than winning

- Letting the other person keep dignity, even in disagreement

This is the balance:

“I will not hide my truth, and I will not harm you with it.”

That balance — courage + care — is the emotional core of harmony.

3️⃣ The Habit of Repair (Over and Over)

Here’s the big one:

Harmony is built less by never hurting each other and more by repairing quickly when we do.

This must be practiced persistently:

- Noticing when distance appears

- Bringing it up gently

- Apologizing without excuses

- Listening to impact without defending intent

Groups that only “get along” avoid rupture.

Groups that develop harmony become skilled at repair.

Repair turns mistakes into deeper trust.

4️⃣ The Discipline of Listening to Understand

Most people listen to respond, defend, or fix.

Harmony requires listening to learn how the world feels from inside the other person.

Practice:

- Letting someone finish fully

- Reflecting back what you heard

- Asking, “Did I get that right?”

This reduces imagined threats and builds real understanding.

Understanding doesn’t always lead to agreement —

but it makes respectful coordination possible.

5️⃣ The Willingness to Adjust, Not Just Be Right

Getting along says: “Let’s not make waves.”

Harmony says: “Let’s keep tuning.”

This requires asking regularly:

- “What small change would help us work better?”

- “Where might I need to flex a little?”

Harmony dies when people cling to:

- Roles

- Pride

- Being right

- “That’s just how I am”

Harmony grows when people value relationship health over ego stability.

🧭 The Most Essential Practices (If We Boil It Down)

If a group could only focus on a few things, these matter most:

1️⃣ Speak truth with care

2️⃣ Listen to understand, not win

3️⃣ Repair quickly and sincerely

4️⃣ Adjust instead of hardening

Do these consistently, and harmony will slowly emerge — even among very different people.

Harmony develops when people repeatedly choose honesty over comfort, care over ego, and repair over withdrawal.

That’s the long road from “we don’t fight”

to

“we can face anything together.”

______________________________________________________________________________

🌿 Harmony Reflection Practice

A Simple Rhythm for Staying in Right Relationship

⏳ Step 1 — Appreciation (Start with Connection)

Each person shares:

“One thing I appreciated this week was…”

This:

- Softens defensiveness

- Reminds everyone the relationship has value

- Builds emotional goodwill before harder topics

Harmony grows faster where appreciation is spoken, not assumed.

🔍 Step 2 — Awareness (Notice the State of the Relationship)

Each person reflects briefly:

“One moment I felt especially connected was…”

“One moment I felt a little distant or tense was…”

No blaming, no long stories — just naming experiences.

This builds emotional honesty without drama.

🗣 Step 3 — Understanding (Listen Before Fixing)

If someone shares a moment of tension, others respond only with:

- “Tell me more about that.”

- “What was that like for you?”

No defending yet. No correcting facts. Just understanding.

Harmony grows when people feel heard before solved

🔧 Step 4 — Adjustment (Small, Doable Changes)

Ask together:

“Is there one small thing we could try this week to make things work better?”

Examples:

- “Let’s not interrupt each other in meetings.”

- “Let’s text if we’re running late.”

- “Let’s check in midweek, not just when there’s a problem.”

Harmony thrives on small course corrections, not grand reforms.

❤️ Step 5 — Recommitment

Close with a simple shared statement:

“We’re on the same team. Thank you for staying in this together.”

This reinforces belonging, even after hard conversations.

🌱 Ground Rules That Make This Work

- Speak for yourself, not for others

- No interruption

- No sarcasm or scorekeeping

- Pause if emotions run too high

- What’s shared here is treated with respect

🌟 Why This Practice Works

It trains the exact muscles harmony needs:

| Practice | Harmony Skill Built |

| Appreciation | Positive emotional bond |

| Naming tension early | Prevents silent buildup |

| Listening first | Reduces defensiveness |

| Small adjustments | Keeps system flexible |

| Recommitment | Strengthens shared identity |

Done regularly, this turns conflict from something scary into something manageable and connective.

___________________________________________________________________

Closing Line You Can Use Every Time

“Harmony isn’t the absence of strain — it’s the way we keep tuning, together.”

🌿 Option 1 — Gentle & Grounding

English:

May we stay honest, stay kind, and keep adjusting together.

Chinese (Simplified):

愿我们真诚相待,心怀善意,彼此调和前行。

🌱 Option 2 — Emphasizing Togetherness

English:

We are different, yet we belong together — let’s keep tuning our lives in harmony.

Chinese:

我们各不相同,却彼此相属——愿我们不断调和,共同前行。

🌊 Option 3 — Focus on Repair & Continuity

English:

If we fall out of tune, may we listen, adjust, and find each other again.

Chinese:

若有失和,愿我们彼此倾听,重新调整,再次相连。

🌟 Short, Motto-Style Version

English:

Different hearts, one harmony.

Chinese:

心不同,和为一。

🌿 Daily Harmony Closing Line (Bilingual)

English

May we stay honest, stay kind, and keep adjusting together.

Chinese

愿我们真诚相待,心怀善意,彼此调和前行。

🪵 8-Character Carving Maxim Options

Option 1 — Focus on Relationship

同心調和共行

Pinyin: Tóngxīn tiáohé gòng xíng

Meaning: With united hearts, we harmonize and walk together.

Option 2 — Focus on Ongoing Adjustment

和而不同同行

Pinyin: Hé ér bù tóng tóng xíng

Meaning: In harmony without sameness, we move forward together.

(Inspired by a classical Confucian idea — very culturally resonant.)

Option 3 — Focus on Mutual Care

真誠善意共和

Pinyin: Zhēnchéng shànyì gòng hé

Meaning: With sincerity and kindness, we create harmony together.

_____________________________________________________________________

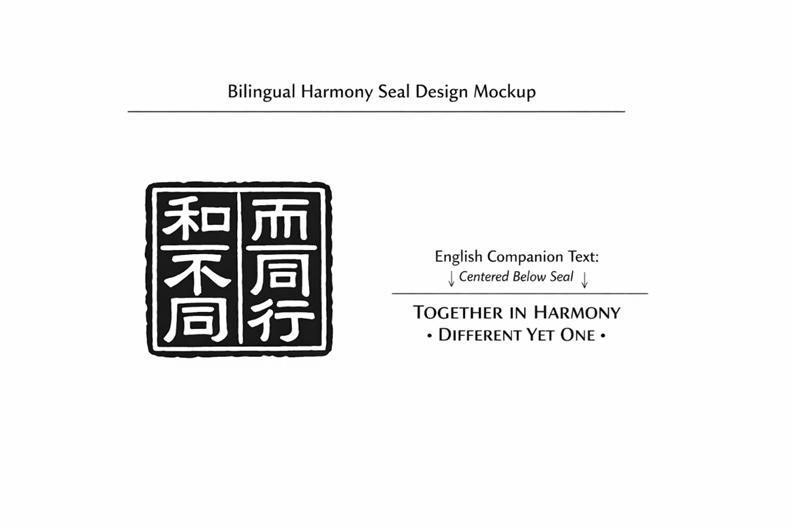

Unity Seal (Symbolic of Wholeness)

和 而 不 同 同 行

TOGETHER IN HARMONY • DIFFERENT YET ONE